Volcanic Soil, Ancient Forest, Open Ocean

Madeira and the Azores reveal Portugal at its most elemental volcanic islands shaped by ocean winds, terraced fields, and slow island rhythms, where nature, tradition, and isolation define everyday life.

Portugal’s Atlantic islands, and the isolation that shaped them

The Azores and Madeira exist because of volcanic activity that happened millions of years ago in the middle of the Atlantic, creating archipelagos that belong geographically to nowhere.

That distance did something to them.

It created islands where European, African, and American influences converged, where endemic species evolved independently, and where agriculture learned to work with volcanic terrain and Atlantic weather rather than against it.

What follows is an exploration of how remoteness shapes life on the Atlantic edge, through volcanic vineyards, laurel forests that predate the Ice Age, marine ecosystems where whales migrate past black cliffs, and farming traditions built for terrain that resists cultivation.

Isolation as a laboratory.

Pico Island: wine from black stone

Pico’s vineyards shouldn’t exist.

Volcanic rock covers the landscape, sharp basalt that cuts through boots, soil so thin it barely qualifies as agriculture. And yet vines grow here, planted inside small stone corrals called currais, built to shield them from Atlantic wind and salt.

The wine tastes like the conditions that made it.

Mineral tension from volcanic ground. Saline notes from ocean proximity. High acidity from cool Atlantic temperatures. The work required to maintain these vineyards is relentless. Harvest means scrambling across rock and carrying baskets by hand because machines cannot navigate the terrain.

Pico became a UNESCO World Heritage landscape not because it is pretty, but because it records human persistence against impossible conditions.

Families maintain plots their ancestors planted centuries ago. They rebuild stone walls after winter storms. They replant vines killed by salt spray.

If you spend time with a small producer here, you start to understand why Pico wine is not a curiosity.

It is terroir at its most extreme.

You might taste Verdelho and see why this grape thrived here even as it disappeared from much of mainland Portugal. You might step into volcanic rock cellars where temperature stays steady year-round, and realise how much of this island’s wine culture is built around adapting to what the land allows.

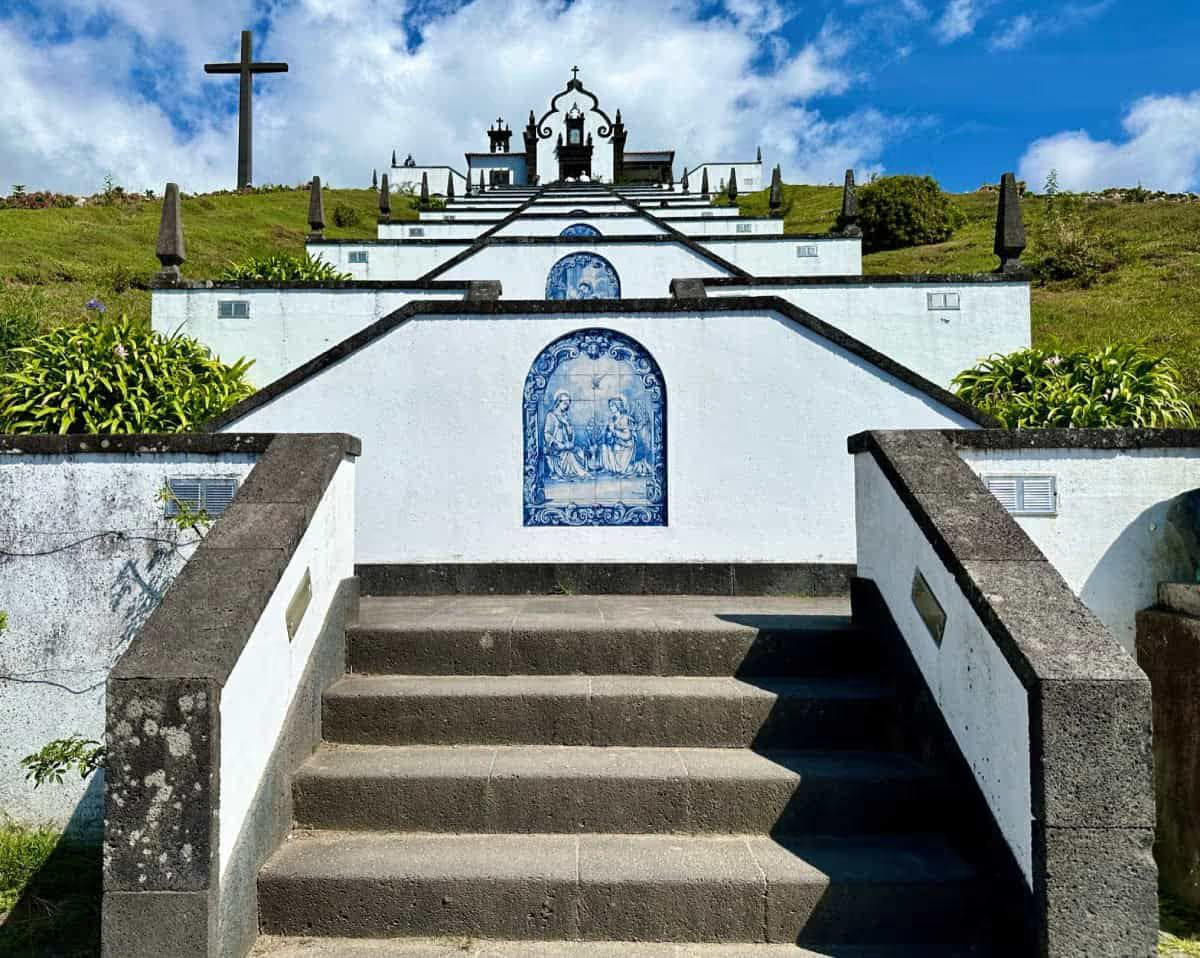

The Azores: where geology is visible

The Azores sit on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where tectonic plates meet.

This is not distant, academic geology. It is active.

Hot springs bubble up through rock. Calderas still breathe sulphur. Lakes fill volcanic craters, their water turned turquoise by mineral content.

Sete Cidades on São Miguel makes that visibility almost too literal. Two lakes, one blue, one green, sitting inside a massive caldera. The colour difference comes from algae responding to different mineral concentrations.

Standing at the crater rim, you are looking at volcanic formation rendered in colour.

In Furnas Valley, the island’s heat becomes part of daily life. Thermal springs, fumaroles, and mineral-rich ground shape how people cook, bathe, and farm.

Gorreana, Europe’s only tea plantation, grows because volcanic soil provides the drainage tea plants need. The processing remains traditional, withering, rolling, oxidation, drying, producing green and black teas with a clean, mineral edge.

And then there is cozido das Furnas, pots buried in geothermally heated ground and left for hours while volcanic steam cooks meat and vegetables.

It sounds like novelty until you realise it is simply adaptation to available energy, practised for generations.

The ocean as neighbour

The Azores sit in the middle of whale migration routes.

Sperm whales, blue whales, fin whales, dolphins, they pass these islands travelling between feeding and breeding grounds. The proximity is unusual. You can watch animals the size of buses surface not far from shore.

That created a relationship with the sea that goes beyond spectacle.

The Azores had active whaling until the 1980s. Many former whalers became naturalist guides, using the same spotting techniques to locate whales for observation rather than hunting.

Their knowledge is not theoretical.

It is built from decades of watching ocean conditions, reading the surface, predicting where pods will rise.

Underwater, the islands reveal another kind of drama. Volcanic rock creates walls that drop fast, caves where groupers hide, pinnacles where pelagic fish school. The water is Atlantic-cold and often exceptionally clear.

Here, the ocean does not feel like a backdrop.

It feels like the main character.

Madeira: laurel forests and levada culture

Madeira’s Laurisilva forest is a Tertiary-era relic, vegetation that covered parts of Mediterranean Europe millions of years ago, surviving now mainly on isolated Atlantic islands.

Walking through it can feel anachronistic.

Tree ferns. Laurels. Moss thick enough to soften sound. Dampness that seems permanent.

The forest exists because Madeira’s mountains create stacked microclimates. Atlantic weather hits volcanic peaks, drops moisture, and forms cloud forest conditions at specific elevations. In a small area, you move through subtropical coast, temperate middle elevations, and alpine peaks.

Then there are the levadas.

Over centuries, Madeira built irrigation channels to move water from the wet interior to the drier south. More than 2,000 kilometres of channels, carved into cliffs, tunneled through mountains, holding a gentle gradient across extreme terrain.

People often talk about levadas as trails.

They are trails, but they are also functioning infrastructure.

They require constant maintenance. They still feed banana plantations and vineyard terraces. They are the reason much of Madeira’s agriculture exists at all.

Walking beside a levada, you start to notice how the island thinks.

Everything follows water.

Madeira wine: fortification before Port

Madeira wine predates Port, developed through a similar logic, fortifying wine so it survives long sea voyages.

But Madeira went further.

Intentional oxidation. Heat ageing. Decades-long maturation that produces wines capable of surviving centuries.

The process is unusual.

Wine is heated in estufas (hothouses) or left in attics where Madeira’s warm climate naturally warms barrels. Oxidation that would ruin most wines becomes essential to Madeira’s character.

The result is a wine that is almost indestructible. Bottles from the nineteenth century are still drinkable.

If you taste across styles, you begin to understand the internal logic.

Sercial, Verdelho, Bual, Malmsey, each tied to different sweetness levels, each shaped by ageing.

A vertical tasting, ten-year, twenty-year, forty-year, shows how Madeira evolves, how it deepens without collapsing.

It is a wine built for distance.

Island agriculture: adapting to impossible terrain

Both archipelagos developed agricultural systems shaped by volcanic slopes, limited flat land, and Atlantic weather.

The solutions are visible in landscape engineering.

Madeira’s ‘poios’ (agricultural terraces) cover mountainsides in narrow strips, sometimes only a few metres wide. Stone walls retain soil. Channels direct water. Microclimates allow cultivation of crops that feel improbable at these latitudes, bananas, sugarcane, passion fruit.

Azorean agriculture reflects different geography.

Pastures divided by stone walls or hydrangea hedges. Dairy farming on slopes too steep for machinery. Pineapple cultivation in greenhouses, often requiring manual pollination.

These are not museum practices.

They are working systems that prioritise resilience over efficiency.

Why isolation created distinctiveness

The Azores and Madeira show how geographic isolation shapes everything.

Ecology. Agriculture. Culture.

Distance from mainland Portugal forced adaptation. Atlantic weather demanded building techniques that could withstand wind and moisture. Volcanic terrain required agricultural innovation.

The result is island identity that is recognisably Portuguese, but fundamentally distinct.

The language is Portuguese, but accent and vocabulary diverge. Architecture follows Portuguese traditions, but adapts to volcanic stone and exposure. Food shares mainland roots, but leans on island ingredients and island logic.

Isolation also preserved traditions.

Madeira’s embroidery. Azorean Holy Spirit festivals. Boat-building knowledge.

Modern connectivity has changed the islands, flights, internet, EU integration.

But geography remains.

You are still in the middle of the Atlantic, where weather patterns, ecology, and available resources create constraints mainland Portugal does not face.

You leave these islands understanding that isolation is not just distance.

It is evolutionary pressure.

It creates unique adaptations, in wine, forests, ocean life, architecture, and agriculture.

And it leaves you with a simple truth.

Portugal’s Atlantic islands are not a backdrop.

They are laboratories.

For customised Azores and Madeira itineraries:

manish@unhotel.in

Subscribe to stay inspired.

Stories, ideas, and slow journeys - from hidden villages to distant valleys, straight to your inbox.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)