Stone Routes, Paper Memory

The Silk Road in Uzbekistan is not a relic but a living corridor, where caravan cities, craft traditions, and shared meals continue to reflect centuries of exchange, movement, and cultural continuity.

The Silk Road as cultural laboratory

The Silk Road wasn’t a road. It was a network of relationships.

What we call the Silk Road was dozens of routes across Central Asia, where merchants, scholars, artisans, and occasionally armies moved goods and knowledge between China, Persia, India, and eventually Europe.

These weren’t passive trade corridors. They were cultural laboratories, places where techniques and ideas collided, adapted, and turned into new forms.

This isn’t a history lecture. It’s a way of seeing how exchange actually worked, through sites and people who can read the evidence in brick, glaze, paper, and pattern.

Geography as cultural synthesis.

Samarkand: where empires deposited their aesthetics

Samarkand’s architecture is a record of successive occupations.

Alexander the Great established a garrison here in 329 BCE. Arab conquest in the eighth century brought Islamic architectural vocabularies. Genghis Khan destroyed the city in 1220. Timur rebuilt it as his empire’s capital in the fourteenth century, importing craftsmen from conquered territories, Persian tile workers, Syrian glass makers, Indian stonemasons.

The result is cultural layering.

The Registan’s three madrassahs, built in different centuries, share design principles that trace back to Persian courtyard structures, then shift through Timurid innovations, then refine under later rule.

If you walk the square with someone trained to look, you begin to notice how the façade decoration works.

Geometric patterns rooted in Persian tradition. Calligraphic elements shaped by Arab influence. Techniques that echo older Sogdian craftsmanship, the pre-Islamic culture that once dominated this region.

The Bibi-Khanym Mosque, commissioned by Timur after campaigns in India, carries a different kind of ambition. Monumental scale. Vast interior volumes. A sense of architectural theatre.

The Shah-i-Zinda necropolis makes the story even clearer. A street of mausoleums built over two centuries, each solving the same problem, how to create a memorable memorial, with different tile techniques, different proportions, different philosophies.

Not one style. Many.

Paper’s journey west: Konigil and a transferred technique

Samarkand became Central Asia’s paper-making centre through captured technology.

Paper originated in China, where production methods were closely guarded. After the Battle of Talas in 751 CE, Chinese paper-makers were taken west, and the technique began to circulate.

In Samarkand, it adapted.

Mulberry bark replaced bamboo. Local water and fibres changed the feel of the sheet. Within decades, Samarkand was producing paper that travelled across the Islamic world and, eventually, into Europe.

By the nineteenth century, industrial production made traditional workshops economically obsolete.

In the 1990s, a UNESCO-supported project revived paper-making at Konigil village, reconstructing water-powered mills and training craftspeople using techniques documented in medieval texts.

You can still see the full process:

- Mulberry bark soaked and softened

- Fibre pounded into pulp

- Pulp spread on frames

- Sheets dried in the sun

It’s easy to romanticise this. The more interesting point is performance.

This paper takes ink beautifully. It holds calligraphy without bleeding. It ages differently from cheaper industrial sheets. Contemporary calligraphers still seek it out for the same reasons scholars did centuries ago.

A transferred technique, adapted to new materials, still doing its job.

Shahrisabz: Timur’s origin story

Shahrisabz is where Timur was born in 1336.

If Samarkand is the empire’s showpiece, Shahrisabz is the origin story, a place where ambition tries to become permanent.

The ruins of Ak-Saray Palace still hint at the scale. The entrance portal stands massive, and the surviving inscription is blunt: “If you doubt our power, look at our buildings.”

Nearby, the Dorut Tilovat complex holds family mausoleums and an architectural lineage that later travels south.

Timur’s descendant Babur founded the Mughal Empire in India. Timurid ideas, how to support large domes, how to shape interior light, how to organise monumental space, moved with him and evolved.

When people talk about Mughal architecture as if it appeared fully formed, Shahrisabz is one of the places that quietly disagrees.

The region also carries its own textile vocabulary. Local embroidery traditions show variations you start to notice only after you’ve seen enough examples elsewhere.

Bukhara: the conservative archive

Bukhara represents a different kind of preservation.

Where Samarkand rebuilt repeatedly, Bukhara maintained continuity. The city holds a dense concentration of protected monuments, and the urban fabric feels intact rather than reconstructed.

The Ismail Samani Mausoleum, from the ninth century, is Central Asia’s oldest surviving Islamic building. A perfect cube of baked brick, patterned through basket-weave geometry and shadow.

No tile spectacle. No colour.

Just structure.

The Ark fortress has served as a citadel for centuries, rebuilt by successive rulers rather than abandoned. The covered bazaars, trading domes from the sixteenth century, still function as markets.

Not heritage theatre. Working commerce under old roofs.

Bukhara was also an intellectual centre, producing scholars whose work shaped Islamic thought far beyond Central Asia. The architecture reflects that seriousness, madrassahs designed not only for prayer, but for study.

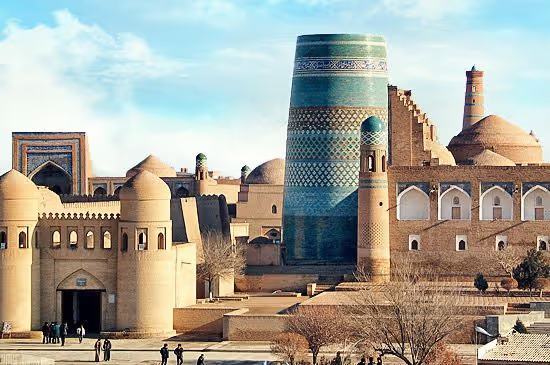

Khiva: the preserved anomaly

Khiva shouldn’t have survived intact.

Remote in the Kyzylkum Desert, shaped by violent politics and a difficult history, it is not the kind of place that usually becomes a preserved city.

In the 1960s, Soviet authorities emptied the old city, restored buildings, and created an open-air museum. After independence, residents moved back.

The result is unusual.

A city that looks frozen in the nineteenth century, but functions as a contemporary community.

Itchan Kala, the inner city, holds a dense cluster of monuments inside walls you can walk across in minutes. The closeness creates constant visual overlap, multiple decorated façades in a single view.

Khiva’s isolation shaped its vocabulary. More compact. More defensive. Less interested in monumental scale. Different colour palettes. A layout that prioritises security.

In and around the city, you can also find revived textile work, including silk carpets made from older patterns documented in collections.

Nukus and the Savitsky Collection: cultural rescue

Nukus sits in Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan’s autonomous region near the rapidly shrinking Aral Sea.

It is remote, economically strained, and rarely on a first-time itinerary.

It also houses one of the world’s great art rescues.

Igor Savitsky, a Russian artist and archaeologist, spent decades collecting works condemned by Soviet authorities as ideologically dangerous. He brought them to Nukus, betting that remoteness would protect what institutions could not.

By his death in 1984, he had amassed a vast collection, including Russian avant-garde works by artists who were executed, exiled, or forced into silence.

Paintings that could not be shown in Moscow hung in a provincial museum in the far west of Soviet Central Asia.

The adjacent Karakalpak State Museum holds ethnographic textiles, rugs, weaves, embroidery, appliqué, from nomadic and semi-nomadic communities with different aesthetics and different constraints.

Here, preservation isn’t about grandeur.

It’s about stubbornness.

Why this corridor still matters

The Silk Road is often romanticised as peaceful cultural exchange. The reality was more complicated.

Empires conquered. Populations were displaced. Resources were extracted. And yet, out of that violence and movement came synthesis.

Timur’s empire was built through military force, but his patronage left buildings that still define Central Asian aesthetics. Trade routes moved silk and spices, but they also moved paper-making, instruments, mathematical ideas, and design vocabularies that travelled far beyond the region.

To understand Uzbekistan’s Silk Road cities, you have to hold two truths at once.

The beauty is real.

So is the history that produced it.

When you walk these routes with people who can decode what you’re seeing, architecture becomes evidence. Craft becomes a record of transfer. A tile motif becomes a clue.

You leave with a different sense of what the Silk Road was.

Not a line on a map, but a corridor of collision and adaptation, still visible in stone, paper, and pattern.

For customised Silk Road and cultural heritage itineraries in Uzbekistan:

manish@unhotel.in

Subscribe to stay inspired.

Stories, ideas, and slow journeys - from hidden villages to distant valleys, straight to your inbox.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)