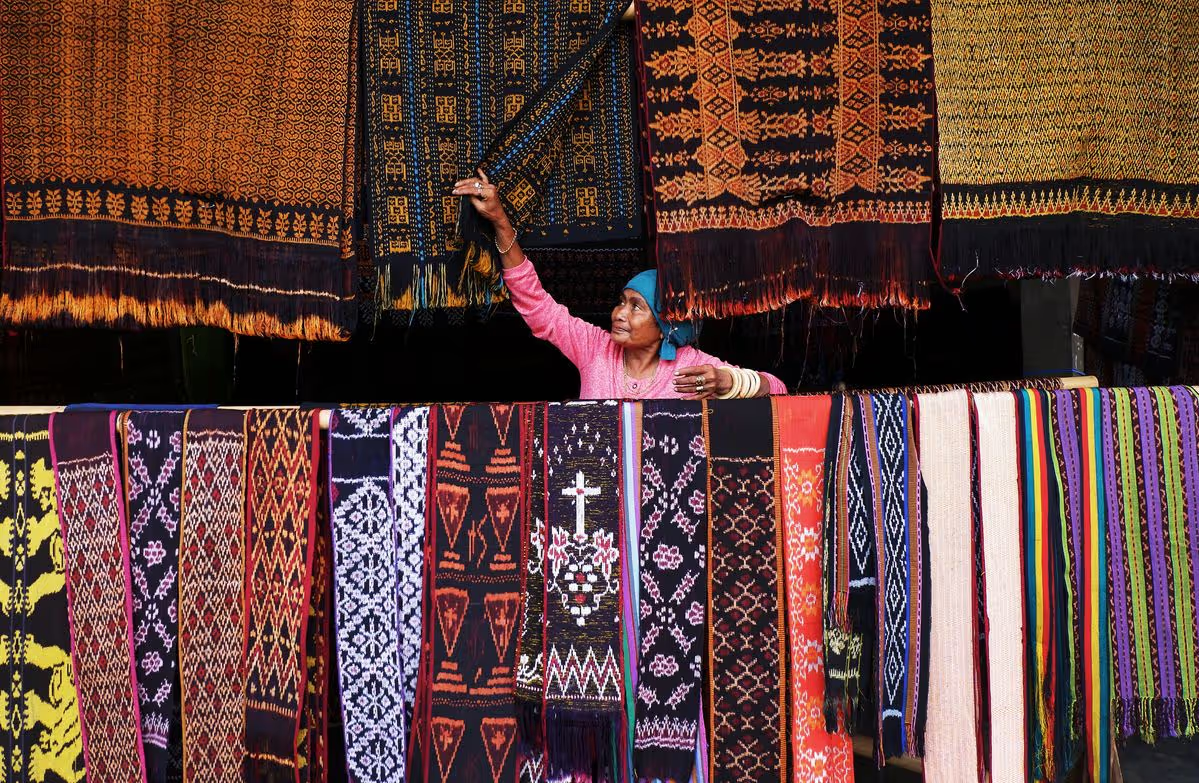

Silk Memory

Uzbekistan’s ikat tradition is a living craft where hand-dyed silk threads create bold, blurred patterns, reflecting centuries of artistry, symbolism, and everyday life along the Silk Road.

Uzbekistan’s ikat masters, and the technique that survived empires

Margilan sits in the Ferghana Valley in eastern Uzbekistan, a silk town shaped by mulberry trees, mineral-rich water, and centuries of trade. If you’ve never heard of it, you’re not alone. But its textiles have travelled further than most travellers do.

Margilan produces some of the world’s most complex silk ikats, and the craft still lives in working workshops, not behind museum glass.

This isn’t a checklist of looms and dyes. It’s a way into a living tradition, held in hands that learned by watching other hands for decades.

Craft as archive.

Margilan: where technique became identity

Margilan’s ikat (hand-dyed woven fabric) tradition didn’t emerge by accident. The Ferghana Valley’s geography created the conditions: mulberry trees for silk, water that takes dye well, and trade routes that brought pigments and ideas from Persia and India.

By the eighteenth century, local weavers had developed abr (cloud) patterns so intricate that reproducing a single design could take months.

Then came Soviet industrialisation.

Collective production replaced family workshops. Synthetic dyes replaced natural pigments. Traditional patterns were dismissed as backward. And yet a few master families kept working quietly, teaching children techniques that weren’t meant to survive.

Today, what’s most striking isn’t nostalgia. It’s continuity.

When you spend time with weavers here, you start to see the logic behind the beauty: why a dye sequence creates depth, how thread tension affects pattern clarity, why certain motifs can only be executed by people with decades of muscle memory.

.avif)

A working silk house: seeing the full process

In Margilan, you can still see silk made end to end.

At a traditional workshop, the process moves at human speed:

- Cocoons are boiled to release the thread

- Silk is reeled onto spools

- Threads are bundled and tied into resist patterns

- Bundles are dyed in sequence, from light to dark

- The final cloth is woven on wooden looms

The point isn’t romance. It’s precision.

This is working production, and the textiles that leave these looms often end up in international boutiques, sometimes without the buyer ever learning the name of the town that made them.

Rasuljon Mirzaahmedov: a master weaver with a global reputation

One of Margilan’s best-known masters is Rasuljon Mirzaahmedov, whose family has maintained traditional ikat weaving across five generations.

His workshop and training centre are also a reminder of how place-based this knowledge is. In the early 2000s, designer Oscar de la Renta commissioned fabrics from him. Not because it was trendy, but because certain technical capabilities exist in specific places, held by specific people.

If you’re lucky enough to spend unhurried time in a master workshop, you see what “skill” really means here.

You’re not watching a demonstration. You’re learning how patterns are built.

How ‘abr’ motifs create optical vibration through calculated asymmetry. Why certain colour combinations only work in specific sequences. How experienced weavers can often tell a fabric’s origin by looking at thread count and dye saturation.

In the same ecosystem, you may also come across kalamkari (hand-printed textiles made with carved wooden blocks and natural dyes). Each colour requires its own block. Registration has to be exact. A single piece can take dozens of impressions.

Machine printing can be flawless. It can’t replicate the small irregularities that give hand work its texture.

The chemistry of resist-dyeing

Ikat is technically warp-resist dyeing. Threads are tied in patterns before weaving, so certain sections resist dye.

The complexity comes from repetition.

A multi-colour ikat requires multiple cycles of tying and dyeing, usually starting with lighter colours and layering darker tones over them.

Traditional dyes came from specific sources:

- Indigo for blues

- Madder root for reds

- Pomegranate skin for yellows

- Walnut husks for browns

Each pigment needs a mordant (a mineral compound that helps dye bind to fibre). Alum brightens. Iron deepens.

Much of this knowledge was empirical, refined through centuries of trial and observation.

Synthetic dyes, introduced at scale in the Soviet period, were faster and cheaper. But they often age differently. Colours fade more uniformly, without the patina that natural dyes can acquire.

A small number of dye masters have returned to natural pigments, reconstructing formulas that were rarely written down because they were transmitted orally.

You might see pomegranate skins simmering with alum, indigo fermenting in earthenware vats, madder root ground to powder and mixed to a precise ratio.

The process looks old.

The chemistry is anything but.

Patterns as encoded language

Ikat patterns aren’t decorative randomness. They carry meaning.

Motifs can signal regional origin, social status, and ceremonial use:

- Bodom (almond) is often associated with weddings and fertility

- Chillaki (lamp) was used for ceremonial robes

- Shohi (royal) indicated high rank

This wasn’t a vague tradition. It was a visual language.

And like any language, fluency matters. Skilled makers can often read subtle variations that outsiders miss.

You can also see how regional aesthetics differ. Bukhara ikats tend to favour geometric precision. Samarkand designs often lean more organic. Ferghana patterns can show Persian influence through floral elements.

Museums may catalogue motifs. But the ability to read the nuance, the difference between two similar ‘bodom’ patterns from different regions, still lives most reliably inside weaving communities.

Kumtepa bazaar: where tradition becomes transaction

Kumtepa bazaar in Margilan runs on Thursdays and Sundays.

This is where weavers sell directly. The textile section is vast: silk ikats, cotton adras (half-silk fabric), suzani (embroidered textiles), and traditional clothing.

It’s also where you learn how hard it is to judge quality without training.

Factory-made synthetic ikats sit beside hand-woven, natural-dyed pieces. The price difference can be dramatic, but the visual distinction isn’t always obvious unless you know what to look for: thread irregularity, dye penetration, and selvage construction.

If you walk the market with someone who understands textiles, you start to see with different eyes.

Not “shopping help”. Material literacy.

Why this matters now

Uzbekistan’s ikat tradition survived partly because it was too complex to mechanise, and too culturally embedded to abandon.

But survival doesn’t guarantee continuation.

Many master weavers are ageing. Apprenticeship takes years before anyone produces saleable work. Younger people often choose faster-return careers.

At the same time, UNESCO recognition and global fashion interest have created new markets, and new pressures. Some workshops simplify techniques for commercial viability. Others hold the line, adapting carefully.

Natural dye production is being revived, sometimes with modern testing to improve consistency. Masters teach new apprentices while also taking commissions from international designers.

What you see in Margilan isn’t a frozen tradition.

It’s a living practice negotiating contemporary economics while trying to keep its technical integrity.

You leave with a different understanding of value.

Not just why a metre of hand-woven, naturally dyed ikat costs what it does, but what it contains: time, lineage, chemistry, and a way of seeing that can’t be downloaded.

For customised craft and cultural itineraries in Uzbekistan:

manish@unhotel.in

Subscribe to stay inspired.

Stories, ideas, and slow journeys - from hidden villages to distant valleys, straight to your inbox.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)